The Wild Wild West: Space Law

The fast-paced development of space tech has created new use cases, which can no longer be effectively addressed by the existing international laws. But is it a bottleneck for the industry?

Space law remains a relatively new phenomenon, involving a combination of customs, treaties, and domestic policies. Most of them have been criticized for offering aspirational ideas, limited practical guidance, and plenty of uncertainty about space ownership. Nonetheless, the industry is gaining momentum, and it is crucial for governments to agree and provide more clarity on at least key topics such as remote sensing, weaponization of space, private property & mining, space debris, and space tourism.

The first mentions of a need for a regulatory framework that can govern human activities beyond the troposphere apparently go back as far as 1910. Emile Laude, a Belgian lawyer, predicted that humankind would have to address the problem of ownership in space and the use of radio waves. In 1926, a senior official of the Soviet Aviation Ministry, V.A. Zarzar presented a paper at a law conference in Moscow, discussing the limitations of each country’s sovereignty over airspace (i.e., where the international zone begins). Not surprisingly, the discussion did not get much attention from the Communist Party or the international community. In 1957, Theodore von Kármán proposed that the boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space started at 100 km (62 miles) above Earth’s mean sea level; many international organizations use Kármán’s line today, but it is not acknowledged from a legal perspective.

The Outer Space Treaty

The launches of Sputnik 1 and Explorer 1 in the late 1950s finally convinced the international community to set some sort of ground rules for the industry with the Outer Space Treaty (OST), introduced in 1967. The OST provides the basic principles for international space law: no weapons, outer space should be free for all, and cannot be appropriated, etc. However, the treaty uses very ambiguous language and, for instance, does not even define where outer space begins. The document’s ambiguity was surely by design, considering the limited amount of knowledge we had about space at the time. Over time, several key international agreements were implemented to supplement the OST and plug some glaring gaps:

Rescue and Return Agreement (1968) - countries must provide assistance to astronauts in distress and return them back to Earth.

Liability Convention (1972) - states that when harm on Earth is caused by a space-based object, the launching country is responsible for the damage.

Registration Convention (1975) - requires all launching states to notify the UN of any objects they launch and provide the UN with the objects’ orbital parameters

Moon Agreement (1979) - calls for the establishment of an international legal regime that will govern the use of the moon and other celestial bodies. The treaty proclaims that the moon should be used only for civil purposes and that its resources are the common heritage of mankind.

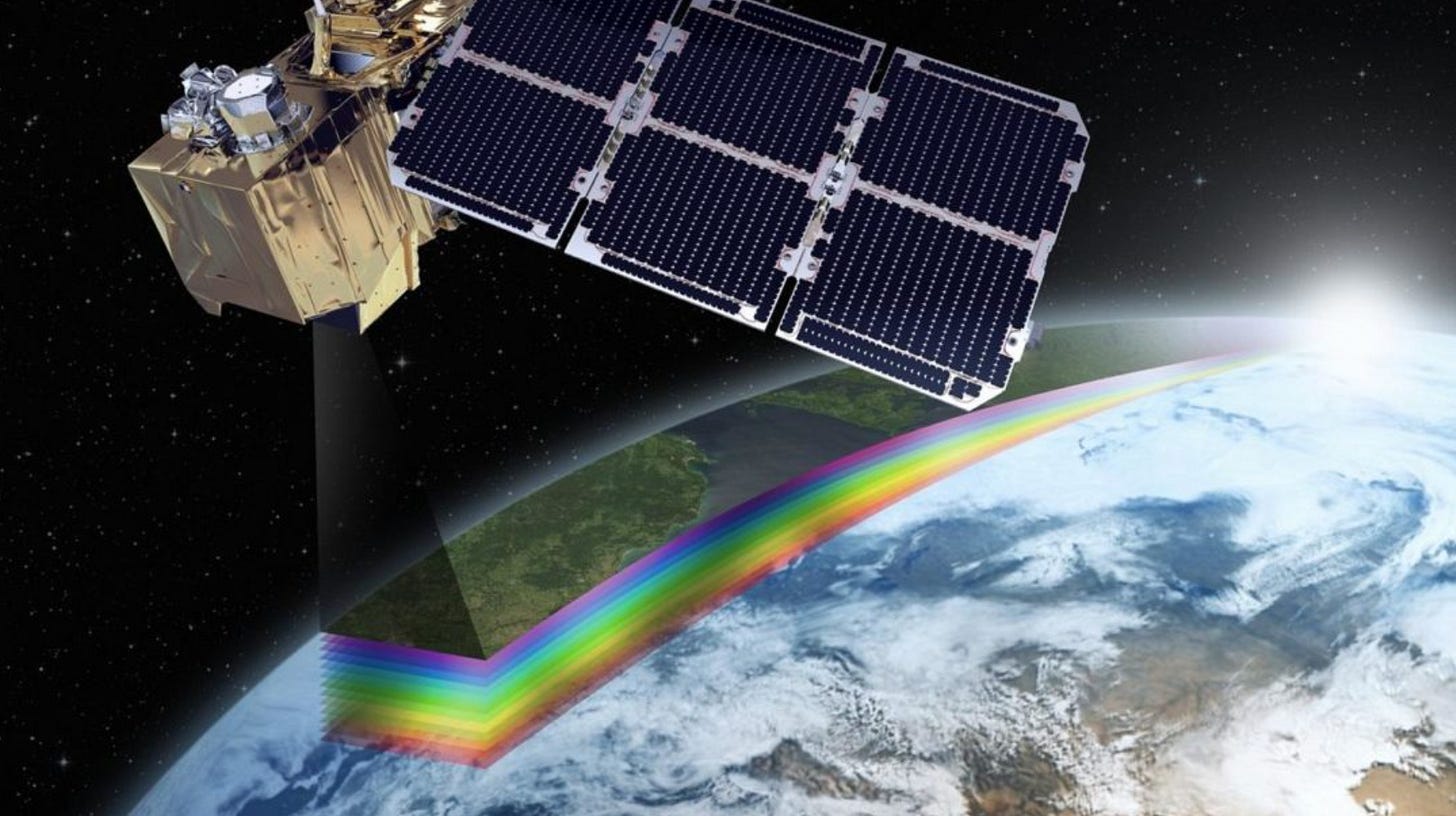

Remote Sensing

Remote sensing is used for meteorology, mapping, urban planning, military reconnaissance, environment protection, ocean topography, and disaster management. In 1986, the UN passed a resolution on Earth Remote Sensing Principles from Space, which is often referred to as a “soft law” and only relevant for applications in civil purposes: natural resource management, land use, and protection of the environment. Militarization of remote sensing (i.e., used for military purposes) is currently not included within the scope, and it is unclear how to regulate dual-purpose satellites. That said, the existing regulation is based mostly on good faith since many countries regularly use satellites for military purposes and are not legally obligated to share collected data. The principles stipulate that Sensing states or private companies do not need prior consent, areas cannot be exempted, and Sensed states cannot veto the observation of their territories. For instance, if a country wants to collect data from Argentina, it would not need Argentina’s consent to do so. Moreover, Sensed states must have access to the data concerning their territory at a reasonable cost and on a non-discriminatory basis, although there aren’t any legal mechanisms to enforce that. Lastly, Sensing states and companies cannot violate the legitimate rights and interests of the Sensed states, yet the principles fail to clarify what actions would constitute such violations in more practical terms. It is worth mentioning that private companies sometimes use remote sensing to spy on competitors or gather intelligence. For instance, a US-based company SpaceKnow often partners with hedge funds, banks, and other parties looking for an edge to provide satellite-based data about virtually anything, anywhere. The conditions level the playing field for all leading spacefaring nations and well-funded organizations but other stakeholders are often disadvantaged.

Weapons in Space

There’s an important difference between militarization and the weaponization of outer space. Space has been militarized for decades since the earliest satellites were launched and used for military purposes. Weaponization, however, refers to the placement of any device with a destructive capacity in outer space. Many experts argue that ground-based weapons with the capability to destroy space-based assets should also constitute space weapons, although they are not technically placed in outer space.

The OST prohibits weapons of mass destruction in orbit, on celestial bodies, or station weapons in outer space in any other manner. Many leading spacefaring countries allow for the possibility that they might be forced to use some kinds of weapons in self-defense. China (2007), the US (2008), India (2019), and Russia (2021) have demonstrated anti-satellite capabilities against their own space-based assets in the last couple of decades, creating vast amounts of debris in the process. In fact, Russia’s current space law recognizes the need and intent to use the space program for military purposes in the name of national security. China, meanwhile, does not have a national space law, but its space agency is deeply intertwined with the country’s DARPA and collaborates on defense initiatives. In 2022, the UN General Assembly approved a resolution introduced by the US to halt anti-satellite weapon tests; Russia and China voted against the resolution, while India abstained. Also in 2022, the UN adopted Russia’s resolution on the non-deployment of weapons in space, yet it is also not legally binding. The only resolutions that have the potential to become legally binding are those that are adopted by the Security Council.

Stationing weapons in outer space goes against everyone’s interests, and it seems that the wheels are slowly turning in the right direction, but it is crucial to introduce comprehensive and legally binding international laws that can ensure the peaceful use of outer space. The issue has become more urgent in light of the dangers posed by cyber warfare. Unless promptly addressed, space-cyber warfare may become the main mode of space warfare in the 21st century.

Private Ownership & Mining

The Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Agreement are the only international laws that provide some information about private ownership in space. The OST states that “the exploration and use of space… shall be carried out for the benefit and use of all mankind”. Moreover, “outer space… is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty” or “by means of use or occupation”. The Moon Agreement holds that there should be an “equitable” sharing of any benefits derived from extraction. Taken together, the laws essentially allow countries to operate in space and seek benefits from space-based operations, while also sharing with other countries. However, China, Russia, and the US haven’t actually signed the Moon Agreement, pursuing their own interpretations of the existing laws. The US believes that the Agreement will “socialize” space-based operations, including resource extraction, prohibiting commercial operations. Therefore, the government enacted the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (CSLCA) in 2015 and Space Policy Directive 1 (SPD1) a couple of years later. Both policies give private companies a right to all extracted resources on asteroids, moons, and planets – but not ownership of the bodies, emphasizing that they are not subject to national appropriation and therefore, do not violate the OST.

Recently, the US passed the Artemis Accords, which aimed to create a framework for cooperation and utilization of space resources. The Accords address many issues ranging from space debris to space traffic, but the document emphasizes that the extraction of resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation. In response, Russia and China stated that the Accords are too US-centric, and the country is pursuing a space version of an “Enclosure Movement'', attempting to claim sovereignty over the moon. However, they are yet to present a viable alternative. In the last few years, Luxemburg (2017), Japan (2019), and UAE (2021) have passed domestic laws that are similar to CSLCA in nature, and more than 20 countries have signed on the Accords. In 2021, Russia and China announced a joint mission to build a base on the moon by the mid-2030s and, as it currently stands, it is likely that all disagreements will be settled through first-mover advantage.

Space debris

The definition of space debris is not actually mentioned in any international laws. The closest applicable term is “space object” which can be applied to any object launched into space. Space debris is not clearly defined because the space treaties were drafted before the spacefaring nations began having concerns over the debris.

Today, there are three treaties with potential relevance to orbital debris issues: the OST, the Liability Convention, and the Registration Convention. The OST declares that countries are responsible for any damage caused by any object (and the components of those objects) that they launch into space. The Liability Convention provides clarification and states that launching countries are liable for any damage caused by their space objects, irrespective of whether the space object causes damage on the surface of the Earth, to an aircraft in flight (Article II), or elsewhere (Article III). The Registration Convention simply requires all launching states to notify the UN of any objects they launch and provide the UN with the objects’ orbital parameters. In addition, the convention directs all nations with monitoring facilities to track and identify space objects that can potentially cause damage.

International law was helpful in addressing the fall of the USSR’s satellite Cosmos 954 in Canada’s territory in 1978. The countries communicated about the potential problem from the start, and there was no question that the falling objects belonged to the USSR. The Canadian government claimed compensation of approximately CAD 6 million under the Liability Convention, becoming the first claim to be filed under the law. The governments reached an agreement that obligated the USSR to pay CAD 3 million, although there was no precise wording regarding the legal nature of the payment, which is why some scholars believe it should be perceived as a voluntary payment rather than compensation for damage. The Liability Convention was used as the legal foundation for the claim and became a vital tool during the negotiations. We expect future international legislation to provide more detail regarding the identification of the causing debris and its launching state because even small debris can cause significant damage to space-based assets, but it is very challenging to determine their source and seek compensation.

Space Tourism

The regulation of space tourism is very market-driven; the US government has allowed industry stakeholders to develop best practices and voluntary standards that can eventually lead to the implementation of a legal framework. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates and licenses all US commercial space launches, but Congress has prohibited the FAA from regulating commercial human spaceflights and thus, the agency has no oversight over the safety of the flight participants. Companies are still obligated to prove that their launch vehicles worked safely during test flights and pose no danger to the public. National legal frameworks regulating private space activities already exist in European countries like Norway, the United Kingdom, and France, but none of these regulations govern commercial human spaceflights. The absence of regulations even requires space tourists to sign informed consent (waiver) in which they accept whatever might happen during the mission. Overall, there’s a belief that any premature regulation will hinder innovation in the industry.

The ecosystem needs more comprehensive international and domestic laws and it is equally important for private companies and governments to continue cooperating on the implementation of market-driven legal frameworks. As far as we can tell, the industry’s technological capabilities remain the main bottleneck, and policymakers will have to react quickly when viable (e.g., space mining) technology is developed in the industry. This is why it is crucial to continue investing in the best and brightest to propel continued innovation in space tech. Stay tuned for another article about space law that will cover domestic policies in greater detail. Meanwhile, shoot alexandra@spaceambition.org an email, if you want to chat about your space tech project or brainstorm ideas!

Thanks for the article. As a rocket scientist I hate dealing with legal issues, while as VC I understand the importance of it. I’m happy that at least someone is working on it:) by the way satellite imaging can help to get insights on your competitors for example you can measure occupation rate of parking lots and forecast the revenue of retail companies. Curious how we treat this situation from legal perspective:)

Many factual mistakes - for example OST doesn't ban all the weapons, but bans only nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction.

Please, check your articles