Venus Exploration: The Rationale for Investment and Missions, and the Objectives of the Search

Scientific interest in Venus has surged, nearly doubling in 4 years. Why do we need to understand Venus’ climate evolution to avoid the same fate for Earth?

Issue 61, Subscribers 9202. With insights from Prof. Jane Greaves (Astronomy, Cardiff University), Prof. Stephen Kane (Planetary Astrophysics, the University of California) and Colby Ostberg (Graduate Researcher, the University of California).

Historic Missions to Venus

For centuries, Venus captured the world's imagination since it's visible to the naked eye, and some cultures associated the planet with the goddess of love, beauty, and femininity.

First discovered in the 18th century, the planet continues to intrigue scientists due to its cloudy atmosphere. They theorize that, because of its dense cloud cover, there may be regular rainfall, and if there's water, there might be life. In 1961, scientists started sending probes to Venus to validate their hypotheses.

Venus became the first planet visited by a spacecraft. In 1962, NASA's Mariner 2 flew past the planet, discovering it as a hot world lacking a magnetic field. Nevertheless, despite these findings, scientists still held hopes for life on Venus. Astronomer Carl Sagan, in a 1967 article, suggested that life forms on the surface, forced to adapt, might have migrated into the skies. If life indeed exists in Venus' atmosphere, it could represent the last remains of a disrupted biosphere.

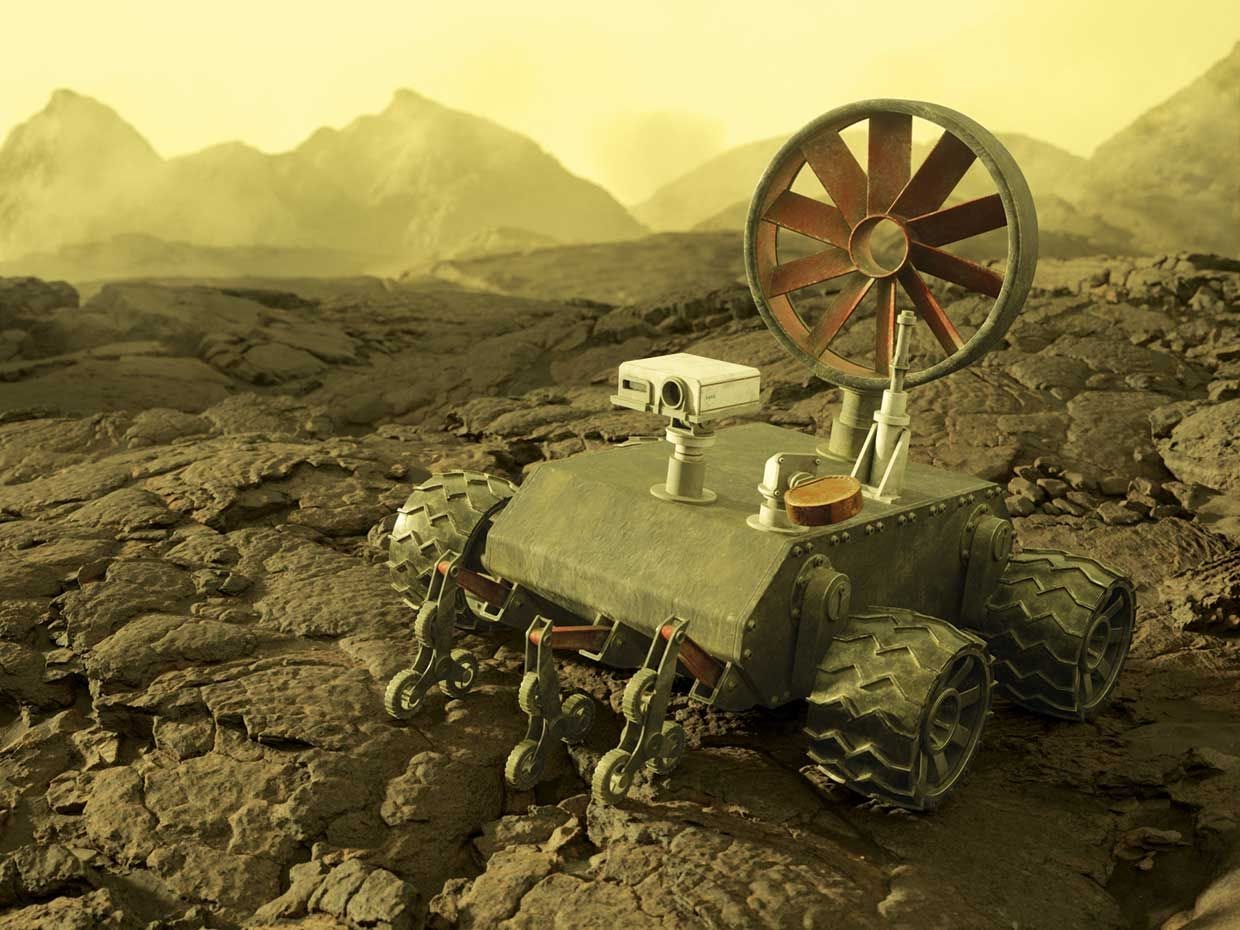

Afterward, the Soviet Union emerged as a global leader in early Venus exploration, dispatching numerous atmospheric probes and up to ten landers to the planet. The first atmospheric studies were conducted in 1967 (Venera-4), the first soft landing in 1970 (Venera-7) which transmitted data back to Earth for 23 minutes, and the last studies on the surface of Venus in 1981. We haven't gotten any data from Venus since then.

To this day, the USSR remains the sole country to successfully land a spacecraft on Venus’s surface and transmit data and images back to Earth. Notably, the initial probes sent to Venus were simply crushed in the atmosphere, as they were not designed to withstand such pressure. The successful missions, “Venera-7” through “Venera-14”, provided us with extensive insights into the atmosphere's composition, climate, and even photographs from the surface of Venus. Of course, there were no such large missions as the Mars exploration mission, there were no Venus rovers, and the maximum operating time of landed stations on the surface of Venus was 2 hours.

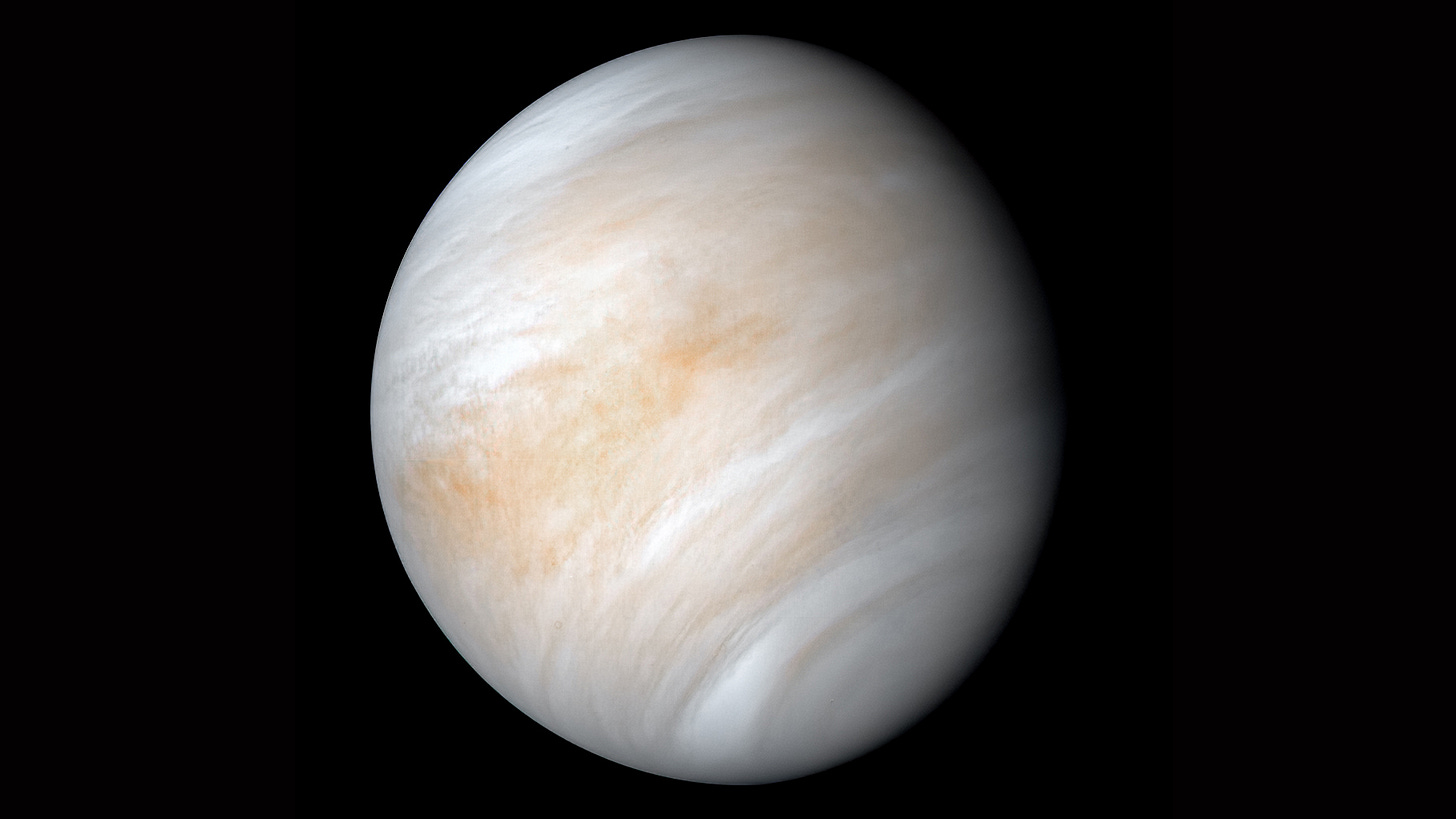

Venus: Heat, Clouds, and Odd Rotation

It's astonishing, but Venus resembles a boiling pot with a lid tightly shut. Due to high concentration of carbon dioxide, Venus experiences a greenhouse effect – infrared radiation (in other words, heat from the Sun) cannot easily escape Venus' atmosphere as the carbon dioxide absorbs this type of radiation and traps it within the atmosphere. This creates a greenhouse-like effect: heat is retained in the atmosphere, leading to the planet's heating.

Consequently, the temperature on Venus reaches 500 degrees Celsius, even hotter than Mercury, despite Mercury being closer to the Sun. Venus's atmosphere is incredibly dense, and the atmospheric pressure is about 90 times (!) greater than Earth's atmospheric pressure. Interesting, that high atmospheric pressure causes the atmosphere near the surface to become supercritical, where the atmosphere behaves more like a liquid than a gas

Atmosphere primarily composed of carbon dioxide (approximately 96%), a small amount of nitrogen (about 3%), and a minute quantity of water vapor (0.003%), Venus also boasts a thick layer of sulfuric acid clouds. Sulfur in the clouds imparts a yellowish hue to Venus. Furthermore, the clouds in Venus' atmosphere move remarkably fast, reaching speeds of 220 miles per hour (350 kilometers per hour).

Interestingly, Venus rotates backward compared to most other planets. This means the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east on Venus. Moreover, this rotation occurs very slowly – just once in 243 Earth days. Venus is the slowest-rotating planet in the Solar System. In fact, a day on Venus is longer than a year on Venus. A year on Venus (its orbital period around the Sun) amounts to 225 Earth days.

By the way, the gravity on Venus is nearly comparable to Earth's due to their similar sizes and masses. Your weight on Venus would be only about 10% less than on Earth. But the 90 bar surface pressure on Venus would prevent you from noticing the lower gravitation.

Venus does not have an internally generated magnetic field like Earth. Instead, it has an induced magnetic field created by the interaction of the solar wind with Venus' ionosphere. This induced magnetosphere is much weaker than Earth's magnetic field. Another interesting fact is that Venus has no moon, as does neighboring Mercury.

Renewed Interest in Venus

It's safe to say that Venus is back in the spotlight, as interest in the planet has sharply surged. At the analytical center of Space Ambition, we've analyzed the number of articles written about Venus in recent years using data from Cornell University's arXiv.org. Surprisingly, the quantity of scientific articles about Venus is now proportional to those about Mars. Moreover, there's a distinct upward trend in the number of publications per year.

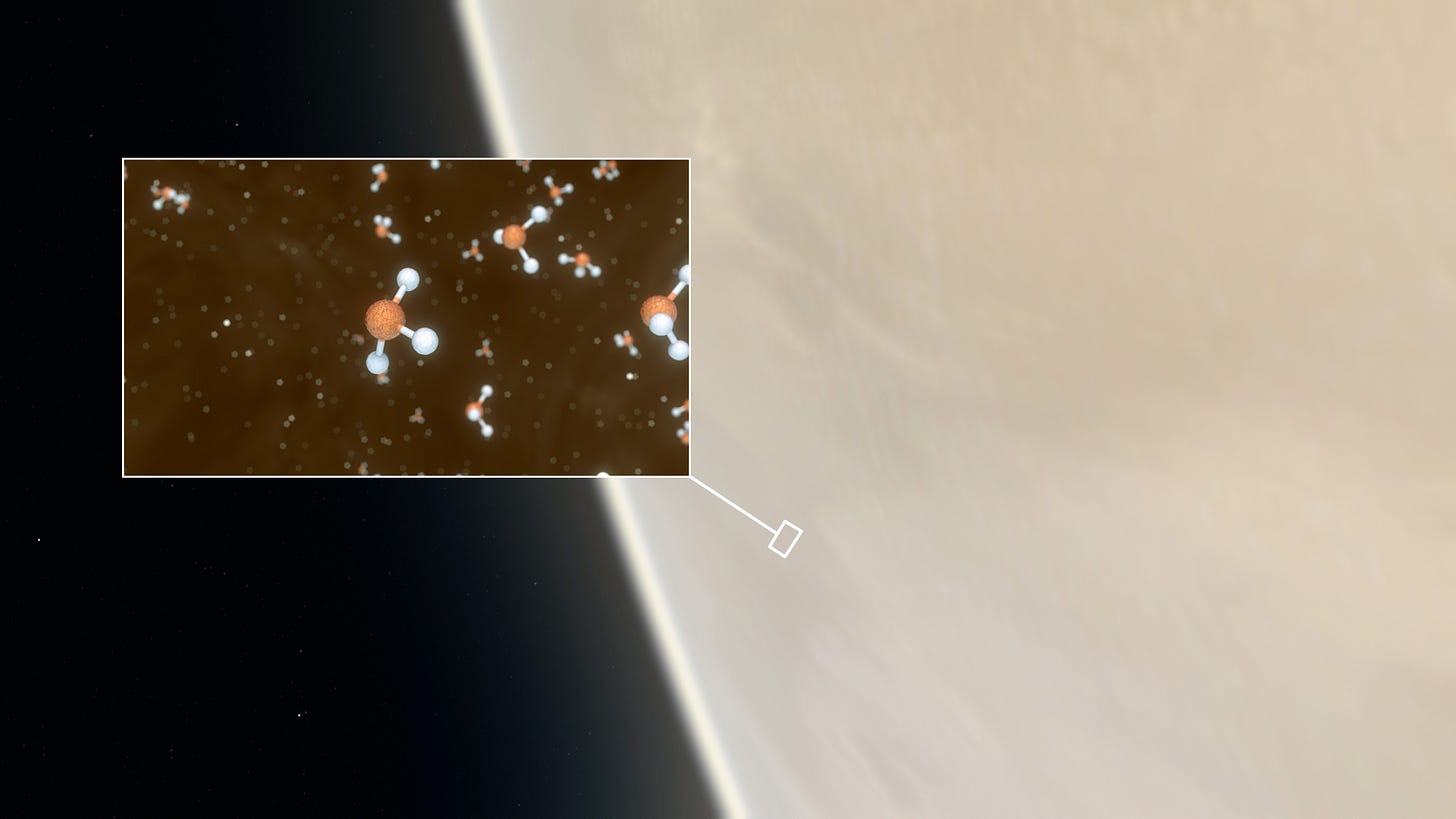

The resurgence in interest could be attributed to several key discoveries made over the past decade, revitalizing enthusiasm. One of the latest breakthroughs occurred in 2020 when scientists announced the detection of gaseous phosphine—an intriguing potential biosignature, a chemical substance closely associated with biological processes—in Venus' clouds at an altitude of 50 kilometers (roughly 31 miles) above the surface. At this height, the temperature and pressure more closely resemble those on the Earth's surface. The presence of phosphine was initially contested, then later affirmed, albeit with an alternative explanation for its origin, subsequently challenged again, and subsequently re-detected in the lower layers of the atmosphere.

We talked with Professor Jane Greaves based at Cardiff University - She led the team that first discovered phosphine on Venus. We asked her if phosphine is really a sign of life on Venus. Here is her answer:

“I'm personally hopeful that life is behind the phosphine on Venus. However, the Venusian clouds are an environment we know very little about, so some other non-life chemistry could turn out to explain the phosphine. The best way forward is to collect more data in-situ, with space probes, especially to search for other signatures of life in the clouds“.

Subsequently, astronomers, employing the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) radio telescope system, detected glycine, an amino acid present in earthly proteins, for the first time in Venus' atmosphere. However, scientists consider this discovery to be controversial.

The discovery of phosphine and glycine molecules in Venus' atmosphere doesn't inherently imply that scientists have found evidence of extraterrestrial life. This discovery merely serves as evidence of a phenomenon that scientists currently cannot explain.

Why Explore Venus at all?

Venus sounds like a very hostile place where we can’t survive. So why do we even need to bother about exploring it?

We talked with Stephen Kane - Professor of Planetary Astrophysics at the University of California and we asked him this question. Here is what he answered:

“Venus is the nearest Earth-sized planet, formed under similar conditions to Earth, and is frequently referred to as "Earth's twin". Yet, we know very little about it. In particular, the nature and timing of how Venus and Earth diverged in climate evolution is fundamental to understanding the concept of planetary habitability, and the subsequent conditions under which life can evolve. By contrast, the search for life largely involves studying planets that we can't see that are many light years away. If we cannot answer fundamental questions for our own twin planet, then there is little hope that we can adequately address primary issues for exoplanets. Additionally, the climate evolution of Venus forms an important component of predicting Earth's future, and whether our planet may eventually suffer the same fate. Venus has a vital story to tell regarding the evolution of a habitable planet, from starting conditions that may have been similar to Earth, through a period of temperate climates, to an eventual fall into post-runaway greenhouse calamity. It is critical, now more than ever, that we consider that story carefully”.

In reality, we can learn many things we can even apply on Earth. The main reasons to explore Venus are:

Scientific understanding: Studying Venus can deepen our comprehension of planet formation and development, including processes of global warming and atmospheric evolution. This could expand our knowledge of planetary systems overall and help us understand the factors contributing to Venus's extreme climate. It could also contribute to our understanding of the climate on Earth and help deal with the greenhouse gas effect.

Technological Progress: Developing technologies capable of withstanding Venus's extreme conditions can lead to significant technological breakthroughs. These technologies could be beneficial for future deep space missions and also find practical applications here on Earth.

Searching for life: after all, potential biosignatures have already been found on Venus and it would be good to explore them.

Space is closer than we think; many technologies have entered our lives thanks to space exploration.

Technologies Driven by Venus for Earthly Applications

Technologies developed for the Space Shuttle are utilized in artificial heart pumps. Nike Airmax sneakers incorporate technology from lunar space suits and so on. Check out our article about space inventions around us.

At Space Ambition's analytical center, we conducted research, analyzing key technologies required for Venus exploration and their potential terrestrial applications. To our surprise, humanity has already reaped technological benefits from these explorations. Some inventions are already in use and some we may benefit from in the future.

Microchips and processors

To support missions to the surface of Venus and elsewhere, NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland is developing extreme-temperature integrated circuit technology. The thing is, on a spacecraft or planetary lander, environmental controls to cool electronics take up space and add mass. By eliminating this cooling requirement, engineers can free up space for more scientific payloads and use less energy. Applications for high-temperature integrated circuits include monitoring and optimizing the performance of jet engines, underground exploration for well sites, and molten salt nuclear reactors, to name a few. Or even in data centers training AI that we use every day.

High-temperature batteries

Indeed, one of the key issues that needs to be addressed is the problem of electrical power. Current batteries, when exposed to high temperatures, can undergo thermal decomposition, lose capacity, and so forth.

The unique design feature of the seven Soviet "Venera" stations, which allowed the USSR's spacecraft to survive on Venus for up to 2 hours, was that the electronic components of these devices were housed in special hermetically sealed thermal chambers cooled to -10°C. The presence of these bulky 'thermoses' onboard increased the mass and cost of the devices. However, at that time it was the only way to solve the issue of electronic functioning in extremely hot conditions

Hence, in addition to new microchips, there's ongoing development of new batteries, which, undoubtedly, will also be utilized here on Earth. Our readers from the MENA region understand what we’re talking about here when their phones switch off during a call in the street on a sunny summer day.

Also, we already have several inventions on the subject.

Electricity production

How can we harness energy from Venus beyond existing methods? There are a couple of hypotheses.

Given Venus' incredibly dense atmosphere and perpetual winds, even a slight breeze carries potent energy that could be utilized by wind turbines. This solution allows you to have a renewable energy source without being tied to the time of day.

However, being closer to the Sun than Earth, Venus receives a denser solar flux. However the thick clouds obstruct efficient solar energy collection. Scientists propose a potential workaround - capturing a vast amount of visible solar energy above Venus' atmosphere and wirelessly transmitting this energy to the surface using a wavelength more capable of penetrating through the dense cloud layer effectively. If we talk about solar panels in orbit and transmitting it to the land, we can say that engineers discuss similar concepts on Earth. It’s not that we really need to go there to build such tech, but the results of R&D will be definitely applicable on Earth.

Atmospheric transport

The unusual atmosphere of Venus may contribute to the development of atmospheric transportation methods. In order to comprehensively study the atmosphere, a vast array of measurements at different altitudes is necessary. Since at altitudes of 55-75 km, Venus's atmosphere parameters are similar to the Earth's atmosphere (from the surface and up to 30 km), balloons can be used.

In another way - successful test flights of NASA's helicopter, Ingenuity, on Mars in a thin atmosphere have proven beneficial. On Venus, such systems would be even more effective due to the higher atmospheric density. Additionally, scientists are exploring wing-flapping systems. They've investigated devices resembling bumblebees and hummingbirds, with wingspans ranging from 30 millimeters to 30 centimeters, and have demonstrated their efficiency.

Looking at more conventional means, even vehicles with limited aerodynamic capabilities can maneuver easily within Venus' atmosphere. Hence, it is foreseeable that Venus' atmosphere will be explored by mini-planes.

Here's what the Professor Jane Greaves thinks about what technology from Venus we can use on Earth:

“As an example, technology to investigate gases coming from any active Venusian volcanoes could be equally useful on Earth. Maybe the tech development will actually be the other way round, but sampling terrestrial volcanic plumes for dangerous gases could help to save lives here”.

Future plans

We talked with Colby Ostberg - Graduate Researcher, Earth and Planetary Sciences Dept. (University of California) and asked what knowledge the upcoming missions to Venus would bring us:

“Our current understanding of Venus’ atmosphere and surface derives from 30+ year old data from the Magellan, Venera, Vega, and Pioneer Venus missions. For context, if we were to image the surface of Earth with the same resolution as Magellan imaged the surface of Venus, we would not be able to resolve the San Andreas fault. The far more detailed measurements that will be taken by the fleet of upcoming Venus missions including VERITAS, DAVINCI, and EnVision will help constrain whether Venus had large amounts of water in the past, provide vastly improved surface and topography maps of Venus’ surface, and give insight into the state of Venus’ interior. The combined efforts of these missions will not only help understand Venus’ past, but may also discover properties and features of Venus that we never anticipated finding”.

The next mission to Venus will be launched by India in December 2024 - the Shukrayaan Venus Orbiter by ISRO. India will launch a Venus orbiter, equipped with radar and an infrared camera to map the surface. The cost of the upcoming mission will range from $60 million to $120 million, depending on the level of equipment.

Unfortunately, there are no other scheduled launch dates for missions to Venus yet - they are all in development:

2029 - NASA DAVINCI. It consists of an orbiter and a reentry probe. The probe will make high-precision measurements of gaseous impurities in Venus' atmosphere and obtain high-resolution pictures of the geological features (tesserae) of Venus, which will help to better understand how terrestrial planets are formed.

2030 - NASA VERITAS orbiter will map infrared emissions from Venus' surface to determine its rock types, which are largely unknown, and determine whether active volcanoes are ejecting water vapor into the atmosphere and study tectonic plates.

NASA is allocating about $500 million per mission for development.

2030 - Roscosmos Venera-D is a continuation of the Soviet mission chain. Assumes long-term stay on Venus (2 weeks).

2031 - ESA EnVision mission. The orbiter will provide a comprehensive view of Venus, from its core to the upper atmosphere. Cost - $653 million.

We asked Professor Stephen Kane what he thought about possible life on Venus:

“There are two kinds of Venus colonizing that one could consider: cities in the clouds or terraforming the planet to make the surface habitable. Cities in the clouds are a more near-term goal. However, the consequences of such a cloud city losing altitude would be extremely severe for the occupants, and I'm not convinced that anyone would want to take that risk. Terraforming Venus presents many significant engineering challenges that would need to be undertaken over several generations. A giant starshade that blocks sunlight from reaching the planet could cool the planet down until the CO2 rains out of the atmosphere. However, one would then need to deal with the vast amount of dry ice, and you would still be left with a dry planet with slow rotation. Terraforming Venus is "playing on hard mode", so to speak, and is an interesting challenge, but not one I find particularly realistic”.

Exploring Venus is not just a step into the uncharted depths of space; it's an opportunity to create something extraordinary. It's a chance to develop technologies that will transform our understanding of what's possible. And who knows, perhaps within those golden clouds and chaotic gases, we might find the key to saving our planet from climate crisis.

May this Thanksgiving be filled not only with the joy of what we have but also with hope for what we can create together, even where it seems impossible.

If you'd like to share your thoughts on Venus exploration, and the commercialization of Venus-related technologies, or if you simply want to extend Thanksgiving wishes, feel free to reach out to us at hello@spaceambition.org.