Spotlight: John Bucknell – CEO of Virtus Solis

Learn about Virtus Solis, a pioneering company developing space-based solar power satellites to democratize energy and tackle global energy challenges.

Issue No 46. Subscribers 7170.

In this month’s Spotlight, we are featuring John Bucknell, CEO of Virtus Solis. We met John at a space tech event a couple of months ago and were blown away by his vision and the team’s experience. His company is building the first solar power satellite that can potentially disrupt the energy industry as we know it and accelerate the transition to clean, sustainable, and – crucially – economic energy.

We delve into various topics, including the challenges pervading existing energy sources, John’s transition to space tech, the inspiration behind launching the company, and much more.

What problem is Virtus Solis solving?

Humanity finally has an opportunity to expand off the planet and make prosperity available to everyone. Global prosperity has increased dramatically over the last 200 years since the advent of fossil fuels, and I would like to see that progress. Low-cost energy underpins everything in our economy. It’s between 10-14% of the global GDP, and if you can get costs down, lots of other things become possible.

All the conventional solutions have significant underlying challenges: easily accessible fossil fuels are not equally distributed and conventional renewables are not available 24/7. There are a few people who control energy, and there’s been resource-related strife for the last 20 years, quite frankly. It is possible to democratize energy by taking the one resource that’s available to everyone – solar power.

The reason I like space-based solar power is the lack of nighttime and weather-related intermittency, which are some of the biggest challenges for renewables. Solar power provides a fascinating alternative because the satellite is above the weather, and the intensity of sunlight is actually 40% better than it is on the ground because the ultraviolet radiation that’s part of the visible spectrum is totally absorbed by the atmosphere. If we can get the power back to the ground in an economical fashion, we’ll basically have a limitless source of energy that can be very low-cost. In short, the genesis and vision of the company are to solve global energy challenges and establish a foothold in space.

Satellite arrays collect solar power and convert it to microwaves. Microwaves transmit solar power to the ground. Ground station rectennas gather microwave energy and convert it back to electricity. Satellites are grouped into massive arrays allowing for a highly scalable energy platform. Arrays can grow to 20 GW or more. Satellites are in sunlight all of the time with long dwell time over the northern/southern hemisphere. Microwaves pass through the atmosphere and weather with nearly no loss. Energy can be sold into the power grid or supply high-demand users with energy directly.

How did your transition to aerospace come about?

As a student of technology history, I was interested in doing something space-related because I have a background in space, just like my dad, who worked on the Apollo program. I wanted to enter space tech in the mid-90s, but opportunities were thin on the ground. If I had wanted to enter in the mid-90s, I would have had to work on missiles. Therefore, I bided my time and waited until opportunities presented themselves.

Not sure if you know anything about the history of Tesla, but in the beginning, they prided themselves on not having anybody with an automotive background. Later, they figured out that engineers weren’t any less knowledgeable in Detroit than anywhere else and had an immense amount of industry-specific knowledge that’s not available in textbooks. In fact, there are more engineers in Detroit than anywhere else, on a per capita basis. So, about 5-6 years into the business, Tesla started hiring automotive professionals for performance improvement along the axes of interest, which were commercialization, cost reduction, robustness, and reliability. Musk wanted the same thing for his aerospace business, SpaceX, because all their products looked like boutique prototypes. I was the Deputy Director of advanced propulsion at General Motors at the time and had strong expertise in aerospace already, so they brought me in to run advanced propulsion.

What inspired you to launch Virtus Solis?

My initial plan was to develop a launch vehicle – a vertical takeoff and landing rocket with about 10 times the mass fraction to orbit of any conventional launch. When I went for venture capital, there were maybe 120 other startups working in launch. I estimated that I needed about $2B to get to launch and have a commercial product. Although there was some interest from investors, we decided to pivot and considered various verticals. Internet of space was heavily saturated and very hard to enter, with a lot of spectrum allocation challenges. Earth observation was also heavily subscribed. There's space tourism, but it has a very small market, is very expensive to do, and only a small number of people can access it. There's mining, which is also not commercially viable yet.

Then there's this other technology that captured my attention – space-based solar power. Peter Glaser did the first engineering proposal for space-based solar power while working as a subcontractor at NASA in 1968. Actually, Isaac Asimov wrote a short story in 1941, describing space-based solar power as part of a storyline that became part of the iRobot series, but no one had done a downtown engineering proposal until the late '60s. There was about a decade of development on that technology, including a team at Princeton, trying to figure out what to do with it – if it's a commercial product, you've got the entire planet as your customer.

I wanted to understand why it didn't work, researched the technology, read more than 170 papers, and decided that not only technical obstacles were mostly obsolete, but also space-based solar power didn't require any new core technology to work. Everything since Sputnik has made it technically feasible but not economically viable, or it hadn't been in the proposals that NASA did. In fact, NASA had an enormous project that involved more than 400 people and wrote extensive engineering studies in collaboration with Raytheon and other subcontractors. But they didn't have access to supercomputers back then and were dealing with slide rules and punch cards. Commercial space launch, especially with the advent of the Falcon Heavy in 2018, superior semiconductor development, Moore's Law, and low-cost manufacturing, has made space solar power economically viable.

I also realized that I had the perfect background to start the company. Someone who would pursue this had to have a background in manufacturing, energy, and aerospace. My previous startup was in the metal additive manufacturing space, making structural components, and using artificial intelligence to automate robotic assembly. I had experience in aerospace, obviously, and worked on energy systems during my time in the automotive industry.

Is your company facing any immediate regulatory roadblocks?

In terms of regulation, I’d argue it’s the “wild west”. There are just two key aspects, and we are making good progress on both of them: radio transmission license and commercial license. We’ve already obtained an experimental transmit license for our wireless power transfers, and we are well on our way to securing the commercial transmitter license, with about a third of the process completed.

The fascinating thing is that our power transfer technology, which utilizes microwaves, doesn’t currently exist in the regulatory environment as a definition. So, we are actively working to educate various regulatory bodies and government agencies about the development of our technology. The encouraging news is that a team at Caltech has already gone through a similar process and obtained a limited commercial license, setting a precedent for us. At present, the path looks quite straightforward.

Is the technology cost-effective?

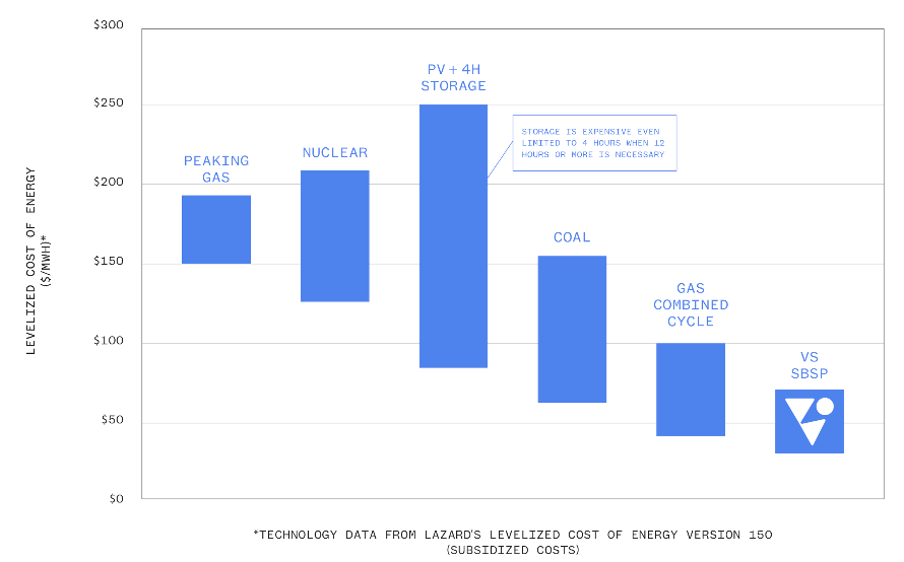

All the evidence points to the fact that this technology can compete with greenfield generation solutions. While it may not be the lowest cost, it is already competitive, and the economic viability has been demonstrated by academia and various consulting companies like Oliver Wyman and Roland Berger. Before that, we conducted our own independent study and concluded that the time to build is now.

Currently, there are two commercial entities, Space Solar and Virtus Solis, operating publicly in this space. The Chinese are also involved in this sector, and there are at least six other startups in the US, along with a few in Europe. As far as we know, they are at the concept stage and don’t have any hardware yet.

It is estimated that the total generation across all forms of primary energy is about 15 terawatts, but the demand is probably 100 terawatts with today's population. The opportunity is enormous, and it is likely that more players will enter the space. We just happen to be the first.

Do you have any advice for our readers and aspiring entrepreneurs?

I’ll say two things. If you want to build a startup, do it early in your career, because it is not as hard. On the other hand, there is a benefit of coming into the startup world with a lot of experience because you understand how organizations are run, which is very hard to learn in school. Organizational challenges are often bigger than technical ones. While technical challenges can be eventually solved if you have talented people, organizational challenges can make or break a business. It is crucial to know how to inspire your employees because they are not in it for the compensation, it is a passion project for them.

On the topic of fundraising, I’ve pitched to 500 VCs in the last four years, maybe a little bit more now. Very few are cognizant of the capital requirements for deep tech startups. However, we think that the software startup industry is going to be decimated by artificial intelligence. There are a few VCs who have woken up to that idea and are essentially pivoting into funding deep tech startups but that might take a little while.

Thank you John for your insights!

Our goal is more than just informing about trends and challenges in space tech; it’s about inspiring entrepreneurs and leaders to act, build, and learn. For every innovator in the sector, there are dozens of skeptics, who claim that the impossible is still impossible. We’d like to see the skeptics proven wrong.

Should you have questions or suggestions, reach out to us at hello@spaceambition.org. We’ll be happy to chat.