Space Data Centers: Promise, Physics, And The Parts That Still Are Not Penciled (Yet)

The buzz is real, and it didn’t come from nowhere

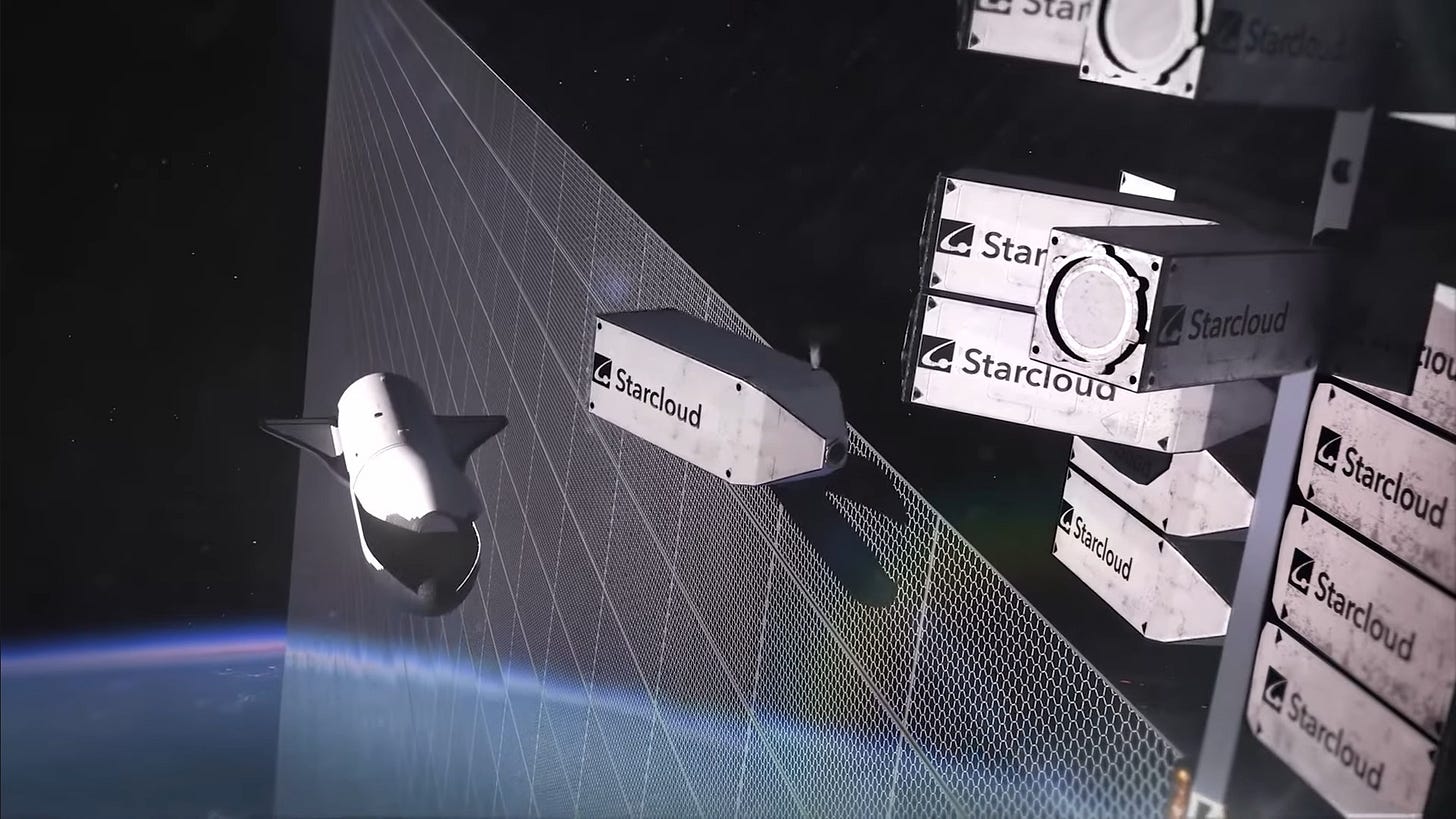

The “space data center” idea has moved from PowerPoint to prototypes because a few concrete events hit in sequence. Europe’s ASCEND feasibility study (2024) explicitly asked whether moving compute off-planet could reduce the footprint of digital infrastructure, and concluded one would need a ~10× lower-emissions launch system before the climate ledger even starts to work. In parallel, startups like Lonestar (~$9 million total funding), Starcloud ($23+ million total funding) ran live storage demos in 2024–2025, keeping the meme in headlines. The market also hints at steady demand: Nvidia and Google just announced their plans to locate data centers (DC) in space. “The lowest-cost way to do AI compute will be with solar-powered AI satellites,” said Elon Musk recently. And the communications side had its moment: NASA’s TBIRD laser downlink moved ~1.4 TB in ~3 minutes at 200 Gb/s.

Why Even Consider Space Now? Because The Earth-Side Constraints Got Loud.

Power demand for data centers is climbing steeply: the IEA’s 2025 analysis projects ~945 TWh by 2030 - roughly a doubling vs. early-2020s levels, with AI as the main driver. This represents just under 3% of total global electricity consumption in 2030, or the consumption of Japan alone. Dublin’s operator EirGrid effectively paused new DC connections until ~2028, a clear example of how networks in developed cities are overloaded. In that context, the notion of harvesting uninterrupted solar energy in orbit and radiating waste heat into cold space sounds elegant. But this comes down directly to physics.

The Physics: Vacuum Is An Insulator, Not a Freezer.

In space, you can’t convect or conduct heat away: you only radiate it, and radiator area scales brutally for multi-MW loads. If you want a back-of-envelope: suppose you want to dump 1 MW of waste heat at 350 K (≈ 77 °C). For a perfect blackbody (i.e., the best-radiating body), Stefan-Boltzmann gives σT⁴ ≈ 0.85 kW/m² ideal. You are looking at ~1,200 m² of radiators per MW, rising fast if you must run colder.

That’s why thermal engineers have chased liquid-droplet radiators (LDRs) for decades: instead of lugging vast panels, you fling controlled droplet sheets that radiate and get recaptured—promising far better mass/area efficiency, but still developmental (splashing, collection, contamination, solar back-loading). Conventional panel radiators work, yet they become the dominant mass for power-hungry systems on a large scale. Cooling, not only chips, becomes the payload.

The Environmental Ledger (The Quiet Killer).

ASCEND’s headline finding was blunt: even if the operational power is clean solar in orbit, launch emissions and in-space logistics dominate unless launch becomes ~10× cleaner over life-cycle. Meanwhile, on Earth, the policy response to the doubling of DC power consumption by 2030 is to steer construction toward cleaner grids and better placement, rather than moving computing into orbit. In other words, the Earth-based DC keeps improving: if ground DCs keep sliding toward better Power Usage Effectiveness on decarbonizing grids, orbital systems lose a big part of their climate argument.

But Space Is Cold, Can’t We Just Run Quantum There?

Space gives you a radiative sink and allows you to cool down to 2.7K (this temperature is due to the residual heat from the Big Bang, so-called cosmic microwave background (CMB)), but it does not hand you that “for free”: you need to block Sun/Earth/Moon heat. Even the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) needs a dedicated cryocooler to push its instruments below ~7 K; passive shielding alone bottoms out around a few dozen Kelvin. Going below 1 Kelvin (as ESA’s Planck did) requires a dilution refrigerator - complex and, in Planck’s case, consumable. Superconducting single-flux-quantum (RSFQ) logic and most quantum computing stacks, therefore, drag a large cryo power bill (and big radiators to reject it). The enticing device-level energy gains are real, but the wall-plug efficiency, including cryocoolers, remains the determining factor today.

Reliability And The Radiation Reality.

Modern chips are vulnerable to single-event upsets and cumulative dose. There’s still no fully rad-hard datacenter-class GPU. Operators flying сommercial off-the-shelf compute mitigate with shielding, which is good for demos, not yet for hyperscale. (HPE’s Spaceborne Computer-2 on the ISS ran teraflop-class workloads precisely because the ISS provides shielding, power, cooling headroom, and serviceability that free-flyers lack. And space weather isn’t abstract: the Feb 2022 geomagnetic storm deorbited dozens of newly launched Starlinks: a vivid reminder that solar activity affects drag, power, and risk. Just yesterday, a solar flare affected more than half of the A320 fleet, disrupting global travel

Add micrometeoroid and orbital debris (MMOD) shielding and avoidance fuel: both add mass right where radiators make you widest and most fragile.

Where Onboard Compute Makes Sense (Today).

Satellites generate vast amounts of data, much of which may be redundant or non-essential. Processing data in orbit significantly reduces the load on downlink services and infrastructure. Compressing or pre-processing data using AI chips, such as those used by Planet Labs’ Pelican constellation, becomes essential to reduce the volume that must be downlinked.

For example, some satellites can detect and discard images with excessive cloud cover, ensuring only useful data is sent to Earth. Enabling faster delivery of actionable information for time-sensitive applications like disaster monitoring, defense, and maritime surveillance is another niche.

What Would Have To Change For “Space Data Centers” To Move From Curiosity To a Category?

Three levers stand out:

Thermal tech: either LDRs or radically better high-temperature radiators to cut area/mass, with credible MMOD survivability.

Radiation-tolerant chips: datacenter-class GPU/AI silicon with harder shielding or architectures inherently tolerant of Single-Event Upsets.

Launch & servicing: truly low-$/kg and low emissions plus standardized robotic assembly/repair, so radiator hits, array degradation, or battery swaps aren’t mission-ending.

Given the thermal math (radiators dominate), the reliability burden (radiation + debris), and the climate ledger (launch emissions), the “space DCs” will be special-purpose infrastructure until those three levers move.

Orbital compute represents a convergence of physics and stubborn economics. Every year, ground facilities get cleaner grids and tighter power effectiveness; every year, space gets cheaper lift. The crossover point isn’t a law of nature: it’s an engineering and policy race. Which curve bends faster: radiators + robotics in orbit, or grids + siting on Earth? The answer will likely be workload-specific rather than universal - and that is the real insight hiding under the hype. If you would like to continue the discussion and contribute, please email ivan@spaceambition.org. We are always happy to discuss the details.

Thank you so much for writing this article. Trying to cool anything in space “because space is cold” good grief lol.

That really would only work in a place like Antarctica so forget data centers in space data centers in Antarctica is what we need.