How to Invest in Space Tech: The Case of Rocket Lab

VC is an expensive education, as you learn from both your successes and mistakes. Today, we will dive into the decision-making process of Bessemer Venture Partners, which invested in Rocket Lab.

Issue 89. Astronauts 11 434.

We invite you to join the first professional investment community on AngelList focused exclusively on space tech investments: Beyond Earth Technologies

One of the goals of Space Ambition is to support current and future space tech investors. This is why our co-founder, Denis Kalyshkin, decided to explore the case of Bessemer Venture Partners' investment in Rocket Lab in October 2014. For this analysis, we will use their investment memorandum, as well as other public information available as of October 18, 2014. We will also rely on the framework Denis has applied to make investment decisions throughout his 10-year career in VC. By the way, he runs a free course called "VC Analyst," which has taught over 7,000 people how to invest in startups. You can watch his webinar to learn more about the framework.

We hope this article will help you better understand how VCs make decisions and what they pay attention to. To further understand their logic, we encourage you to read our Space Tech VC Spotlights and Series A overview for 2023. If you want to learn more about the jet propulsion sector, please read our relevant article here.

About the Deal

Rocket Lab developed a rocket for launching 100-150 kg payloads. As of October 18, 2014, Bessemer Venture Partners planned to lead a $20 million Series B round. Several strategic investors, such as K One W One (which had invested in Rocket Lab's previous round), Lockheed Martin, and In-Q-Tel, also planned to join the round. The government of New Zealand provided financial support in the form of non-dilutive funding, refunding 20% of the company's expenses up to $25 million, adding $4 million to the current round.

As of the date of the deal, Rocket Lab had developed most of the technologies necessary for their first test flight in late 2015 and planned to start assembling the vehicle 3-4 months after the round. They aimed to conduct 3 test flights and 1 commercial flight as part of this round. The current pipeline included 40 launches valued at $200 million. Rocket Lab's founder, Peter Beck, believed that Series B would be the last investment round needed to bring the company to profitability.

The Bessemer team, however, was more conservative. Based on their deep tech and space tech investment experience, they knew that many delays could occur along the way. Therefore, they suggested that the company might need another round of funding. Given that Rocket Lab had previously raised only $5.5 million, raising additional funding wouldn’t significantly dilute the team’s ownership, and they would still be motivated to run the business. The company had already been incorporated in Delaware, making it easier to transact with US VCs.

Rocket Lab History and Private Space Tech Company Landscape

Before we dive deeper into the deal, let's review the state of the market as of October 18, 2014. The New Space Era began in 2010.

SpaceX, founded in 2002, had been on the brink of bankruptcy before its first successful launch on September 28, 2008. Following this, the company was awarded its first $1.6 billion contract from NASA in December 2008. SpaceX subsequently raised over $1 billion in government and private funding, including $250 million from private investors (current investment exceeds $9.8 billion). The company made its first commercial delivery to the International Space Station in May 2012 and reached a valuation of over $2 billion.

Blue Origin, founded in 2000, had its first test flight in 2006. There was limited news about their progress until 2013, when they announced plans for an orbital launch in September 2015.

Virgin Galactic, founded in 2004, raised $100 million from the Virgin Group and an additional $390 million from investors in MENA in 2010-2011. In June 2014, they announced their negotiations with Google about a potential investment.

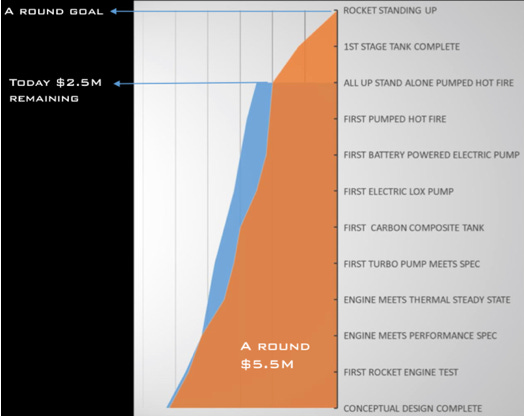

Rocket Lab was founded in 2007. In 2009, they launched Atea-1, becoming the first company in the Southern Hemisphere to reach space. During his trip to the US, co-founder Peter Beck realized there was a niche for small payloads. He also met Mark Rocket, who became his first seed investor and served as a co-director between 2007 and 2011. At Space Ambition, we believe this helped bring necessary business acumen and a network in the US. In December 2010, Rocket Lab was awarded a U.S. government contract from the Operationally Responsive Space Office (ORS) to study a low-cost space launcher to place CubeSats into orbit. They demonstrated their Viscous Liquid Monopropellant for DARPA in 2010 and released a UAV in 2011. They also demonstrated the first 3D-printed engine in 2013. As of October 18, 2014, they had launched 89 sounding rockets over 7 years, carrying scientific instruments to suborbital altitudes as part of an R&D program with DARPA and Lockheed Martin. They raised a $5.5 million Series A round from Khosla Ventures, which helped them make significant technological progress and prepare for the first orbital test flight.

We will discuss other players in the competitor section below. On one hand, VCs saw the first signs of progress for private space tech companies; on the other hand, several leaders had substantial funding. To sum up, despite the existence of several well-funded startups Rocket Lab had an opportunity to build a category leader for small payload launches. They had a strong team that made significant technological progress and worked with DARPA and Lockheed Martin which significantly added credibility to the team.

Problem: Painkiller or a Vitamin

Rocket Lab addressed the growing niche of small payloads up to 100-150 kg. In October 2014, the only available option for clients was "ride-sharing" when larger payloads were launched. In this scenario, they were dependent on the timeline of the main payload's launch, which could easily be delayed for months, significantly impacting the businesses of companies like Planet Labs. Getting to orbit via ride-sharing was a painkiller, not a vitamin, because constellation owners lost money and time due to delayed delivery of paid services. The extreme need for an alternative was validated during interviews with Rocket Lab's clients and Skybox, a portfolio company of Bessemer.

Product

Rocket Lab built rockets with 3D-printed engines capable of sending a payload of 100-150 kg to a 500-km sun-synchronous orbit (ideal for earth observation) on a weekly schedule. The price per launch was $4.9 million or $49,000 per kg of payload. The cost of the rocket was $1 million, allowing for a significant price decrease in the future if competition grew. Their "Electron" was a 2-stage liquid oxygen kerosene rocket that was easy to assemble. They also used a 3D-printed rocket engine, which speeded up production. The carbon-composite tanks made them 40% lighter than aluminum tanks. It had several technical innovations, including all-composite rockets and electric turbo-pumps. These innovations enabled frequent and flexible launch time slots for small payloads. Another innovation was the plug-and-play solution, which allowed customers to prepare their payload and send it to Rocket Lab. This made it easier to change the payload in case of last-minute changes because Rocket Lab always had ready-to-fly payloads from several clients. It gave small payload owners more control over launch timing since they were now the primary payload. The company also benefited from a lower government launch fee of $400,000 in New Zealand compared to $700,000 in the US. Although it was not the lowest price per kg for a launch on the market back then, small payload owners preferred it because of its flexibility and reduced opportunity cost.

Business Model and Go-to-Market Strategy

Rocket Lab charged $49,000 per kg of payload. They sold directly to satellite owners or through launch brokers, providing primary launch services and flexibility for small payloads of up to 100-150 kg. They had already secured commitments for 40 launches, including 6 launches in the first year through brokers.

Market Size, Trends, and Timing

VCs typically prefer to invest in startups with a $1 billion annual Total Addressable Market (TAM). Rocket Lab forecasted that over 5 years, the microsatellite market would need 945 launches of 100 kg satellites. Satellite owners would like to choose non-standard orbits, so they preferred to be the primary payload. This forecast was based on the needs of the biggest constellations and launching brokers (see the graph below). Given the price of $5 million per launch, we could estimate the market to reach $4.7 billion over 5 years, or $945 million annually.

Launching rockets was costly, risky, and prone to significant schedule changes. In 2013, there were 19 launches in the US with an average cost of $132 million. Half of these launches were government-related. SpaceX's Falcon-9 conducted only 3 launches, carrying payloads of 6,000 kg each at a cost of $65 million per launch. Smaller payloads had to resort to "ridesharing" on Falcon-9 or Dnepr rockets. The schedules could easily be altered by primary payload owners, impacting profitability. For instance, Bessemer's portfolio company, Skybox, had encountered such delays multiple times. Space Flight Services, the leading aggregator of secondary payloads, reported 87 payloads scheduled for launch in September 2014, ranging from 5-50 kg, with 50% experiencing delays (including Planet Labs). They indicated growing demand for such services, though this could change in the future. Many clients in the sub-100 kg payload niche were universities and governments.

Competition

As of October 18, 2014, the satellite launch market was not very competitive. The few alternatives available for small payloads included SpaceX's Falcon-9, capable of lifting 6,000 kg, Orbital Science, and the Ukrainian rocket Dnepr. Several other startups were developing their technologies but had not yet launched:

Virgin Galactic focused more on suborbital flights to space at $200,000 each, with a project called Launcher One potentially competing directly with Rocket Lab. According to Bessemer's information, a team of 12 people was working on it. But the project’s success was dependent on the space tourism business.

Firefly was developing a rocket capable of carrying a 400-kg payload. The founder was an ex-top SpaceX propulsion lead, but the rest of the team based on the Bessemer information lacked aerospace experience. Firefly was 24 months behind Rocket Lab in technological development. Their aim was to increase payload capacity to 1,000 kg at a lower cost, indicating they would not directly compete for payloads below 100 kg in the long run.

Bessemer anticipated more competitors emerging in the future, but as of October 2014, none addressed the niche occupied by Rocket Lab. The company benefited from a first-mover advantage since the future competitors would face significant technological barriers. Rocket Lab would have several years to establish themselves as category leaders. They also had ample room to reduce prices for the launch as competition intensified.

Industry Expert and Customer References

Bessemer spoke with three Rocket Lab clients. It's important to approach feedback from current clients cautiously, as they may be more positive than typical clients in the niche. However, such interviews provide valuable insights. Here are key takeaways from the interviews:

Space Flight Services, the leading secondary payload aggregator, reported that in September 2014, 50% of 87 payloads in the 5-50 kg range were delayed, including those of Planet Labs. They believed they could fill 100 kg payloads every two weeks. They emphasized that while they didn't care about the technology, reliable launches at reasonable prices were crucial. We conclude that on the one hand, the market had an immense need for Rocket Lab services, but on the other hand, it would be easier to switch to direct competitors as soon as they emerged which would put pressure on the profit margins in the long run.

BlackSky, a new imaging satellite company at the time, identified a clear need for such services.

Planet Labs, another constellation owner, planned to conduct 20 launches with Rocket Lab. They viewed this opportunity seriously because predictable launches were critical for their profitability. They had even visited New Zealand to explore the launching site and believed Rocket Lab was ahead of other players in the niche.

Investment Trends and Exit Opportunity

This section wasn’t covered in the Bessemer memo, so Space Ambition addressed it based on Denis Kalyshkin's expertise. VCs typically pay attention to whether other VCs are investing in the niche because deep tech startups often require multi-stage investments. As of October 2014, only a few space tech startups had raised significant funding rounds. Only a handful of VCs were actively pursuing opportunities in this niche, making fundraising challenging. However, there was optimism in the market regarding the progress of the private space tech sector, suggesting that generalist and deep tech VCs might be open to investing in space tech companies just to experiment. The timing seemed to be right, but competition among launch companies was expected to intensify in the future.

Another critical aspect for VCs is evaluating exit opportunities. Since the New Space Era began in 2010 and few companies had raised VC funding and none of them exited via acquisition or IPO, VCs needed to make predictions about future valuation and potential acquirers. On the positive side, conglomerates like Boeing, Airbus, or Lockheed Martin could be potential acquirers of such businesses.

Roadmap

Rocket Lab planned to conduct a test flight in late 2015, followed by two additional test flights. By mid-2016, they aimed to launch their first commercial flight. They planned a total of 13 commercial flights by the end of March 2016, which Bessemer viewed as aggressive. They asked their technology due diligence provider to validate the feasibility of this schedule.

Team

Space Ambition believes that one of the main reasons Bessemer invested in Rocket Lab was their team, with founder Peter Beck standing out in particular. At the time of investment, Rocket Lab had a team of 25 employees, all based in New Zealand. 25% of the team members held PhD degrees.

Peter Beck, Co-founder and CEO of Rocket Lab since 2007, impressed Bessemer with his spirit, energy, and vision. He had numerous achievements in New Zealand. He built water rockets as a teenager. He got an apprenticeship at Fisher & Paykel, where he experimented with rockets and propellants, creating inventions such as a rocket bike and jet pack. From 2001 to 2006, he gained expertise in smart materials, composites, and superconductors at Industrial Research Limited. You can read more about Peter in his interview here.

Shaun O’Donnell, who joined the team as GNC Lead in 2007, was responsible for all electronics and software of the rocket. Before joining Rocket Lab, he worked for a small startup designing electronics for GPS-based systems and later founded Novitas Technology Development, specializing in electronics.

Dr. Sandy Tirtey joined the team as Vehicle Lead in November 2013. He brought 12 years of experience in hypersonic technologies to Rocket Lab. With a PhD in aerospace engineering, he began his career in 2002 working on a Mars Sample-Return orbiter.

Solomon Westerman joined as GNC Engineer in December 2013. He brought experience from SpaceX and NASA. At SpaceX, he contributed to Falcon-1, Falcon-9 v1.1, and Falcon Heavy, leading the GNC for the Crewed Dragon capsule. He also had extensive mission operation experience with Dragon C1, Dragon C2, and Falcon 9.

Financial Traction and Client Pipeline

Rocket Lab had commitments for over 40 launches, including signed Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) from key clients such as Planet Labs (20 launches), Surrey Satellites, Weathernews (2 satellites weighing 45 kg each), Outernet, and launch broker Space Flight Services (6 launches planned for the first year). Their pipeline was about $200 million, demonstrating strong commercialization prospects.

Technological Traction

Rocket Lab had previously raised a $5.5 million Series A round from Khosla Ventures when the company was in the conceptual design stage. By October 2014, they had advanced significantly in technology development, having completed most of the necessary technologies. The next milestone was to construct a rocket within 3-4 months, with the first launch planned for late 2015 and the first commercial launch scheduled for 2016. It was believed that the majority of technological risks had been mitigated by this stage.

Barriers to Entry

VCs often ask startups about their "secret sauce" and why their business will be difficult to replicate. This concept is fundamental and extensively covered in microeconomics courses. Simply put, the easier it is for new players to enter a market, the more competition will emerge, leading to lower profit margins over time for each participant.

In the case of Rocket Lab, the primary barrier to entry was the development and successful testing of technology in actual space flights. This hurdle provided first movers with several years of relatively low competition, enabling them to establish themselves as category leaders. On the flip side, clients were less concerned about the technology itself and focused more on reliable launch services at competitive prices. This dynamic would exert long-term pricing pressure, potentially causing many players to go bankrupt as they struggle to secure significant funding. VCs, in turn, would be hesitant to invest in challengers against established category leaders.

Previous Investments and Partners Behind the Deals

It is also valuable to explore the backgrounds of the partners at Bessemer and Khosla Ventures involved in the deals.

Rocket Lab raised a $5.5 million Series A round from Khosla Ventures in October 2013. According to Crunchbase, the deal was led by Sven Strohnband, who at the time was a CTO and partner at Khosla Ventures. Prior to joining Khosla Ventures in 2012, he co-founded a small startup and held a PhD from Stanford in Mechanics & Computation. This deal was one of his first investments at Khosla Ventures. He previously worked for 6 years as a partner and CTO at Mohr Davidow Ventures. So Series A investment was done by a partner with an engineering and entrepreneurial background.

According to the Bessemer memo, the current deal involved two team members: David Cowan (Partner at Bessemer) and Sunil Nagaraj (Principal).

David Cowan has been a Partner at Bessemer since June 1992, overseeing the deep tech portfolio of the fund. He has served as a board member at SkyBox since 2010 and holds a master's degree in Computer Science and Mathematics from Harvard. David also later joined the board of Rocket Lab. So the deal was done by an experienced deep tech partner with a technical background from a prestigious US university.

Sunil Nagaraj, a Principal at Bessemer since 2011. He had an engineering background and startup co-founding experience. He holds a bachelor's degree in Computer Science and an MBA from Harvard Business School. It was his first deal in space tech. He also became a board observer in Rocket Lab later.

Risks

Technological risk. The primary technological risk was the electric turbo pump required to feed the engines, demanding high-pressure fuel at a significant rate. No one had previously developed such technology, but the Rocket Lab team claimed they had achieved a working solution during the Series A phase. To validate this, Bessemer hired a third-party consultant to conduct technical due diligence.

Risk of under-investment due to potential delays in launches. As of October 2014, the company had raised only $5.5 million, despite planning a $20 million Series B round. Government support covering up to $25 million in spending was a benefit for current and future investors.

Business risk was considered acceptable, bolstered by positive client feedback and commitments for 40 launches. The company anticipated its first commercial flight by mid-2016, 1.5 years after the current investment.

Competition. As of October 2014, there was little competition in Rocket Lab's niche, though Bessemer anticipated this would change. The risk was mitigated by their first-mover advantage, advanced technology, and that competitors will need to secure funding for development of the technology.

Risk of clients switching between providers. As of October 2014, clients lacked alternatives, but this was expected to change in the future. This risk was viewed as moderate, as Rocket Lab had flexibility for price reductions (selling rocket launches for $5 million with a $1 million cost).

Summary of Why Bessemer Invested

This is Space Ambition's perspective on why Bessemer invested in Rocket Lab, based on the memo and our expert understanding of VC decision-making and the space tech investment market conditions as of October 2014:

Rocket Lab targeted a niche market with its capability to launch payloads of 100-150 kg, which was growing but underserved by existing players.

Clients had a critical need for Rocket Lab's product, viewing it as essential rather than optional (a pain killer, not a vitamin).

By October 2014, Rocket Lab had advanced its technology significantly. They planned to conduct 3 test flights and a commercial flight by 2015-2016, effectively mitigating technology risks. Though technical due diligence results were pending as of October 18, 2014, we believe they would be satisfactory.

The company secured Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) and commitments for 40 launches, potentially generating $200 million in revenue.

Competition in the targeted niche was sparse; no other players focused on launching payloads of 100-150 kg. High technical barriers to entry ensured Rocket Lab would maintain a first-mover advantage for several years.

Experienced team. Bessemer was impressed by the strong leadership of founder Peter Beck.

Strategic investors planned to invest in the round. One of them was a Series A investor, signaling confidence in the company's performance.

Rocket Lab benefited from non-dilutive financial and non-financial support from the New Zealand government, enhancing profitability and increasing investment amount available for the company.

The company had high margins and significant room for price reductions as competition intensified.

Despite the nascent stage of the space tech VC market, optimism prevailed following the 2008 financial crisis, encouraging VCs to explore new opportunities.

Rocket Lab's collaborations with DARPA and Lockheed Martin added credibility to the startup.

The standardized and easily assembled rocket facilitated weekly launches, demonstrating operational efficiency.

The investment was led by David Cowan, a seasoned deep tech investor and board director at SkyBox, with substantial experience in the space tech market.

You can often hear that investing in hardware is hard. We at Space Ambition share this vision as well. However, we believe the growth of investments in deep tech and space tech is inevitable as software solutions have already solved easier problems. We hope that Space Ambition will support you in navigating this evolving landscape. If you have any ideas or questions, please email us at hello@spaceambition.org.